Editor’s Note: This post was originally published March 2014 and has recently been updated and revised for accuracy and comprehensiveness.

4.5 million shoulder injuries are reported each year and occur primarily in a gym setting. Learn how you can prevent shoulder injuries from happening to you:

The shoulder is an incredible structure. It is complex, versatile and efficient. An expense many times is incurred as a result of these advantages, and it is often a very unforgiving part of the body. Still, many medical professionals agree that the mechanical perfection of the shoulder is unsurpassed when compared to the other joints. For example, the shoulder is the only joint that can rotate 360 degrees, making it the most mobile.

The shoulder joint also allows you to serve a tennis ball, roll a bowling ball, press overhead against resistance and raise your arms out to either the sides or the front of your body while holding dumbbells in your hands. These capabilities make the shoulder joint, the most varied in function. Unfortunately, because of its complexity, it is also the most vulnerable to injury. To understand the shoulder’s complexity and consequent vulnerability, it is necessary to know a little about the anatomy of the bones, joints, and muscular and ligamentous structures. If you are interested in helping people with shoulder and other injuries, our article on post rehab exercise specialists might interest you as well.

Bone and Joint Anatomy

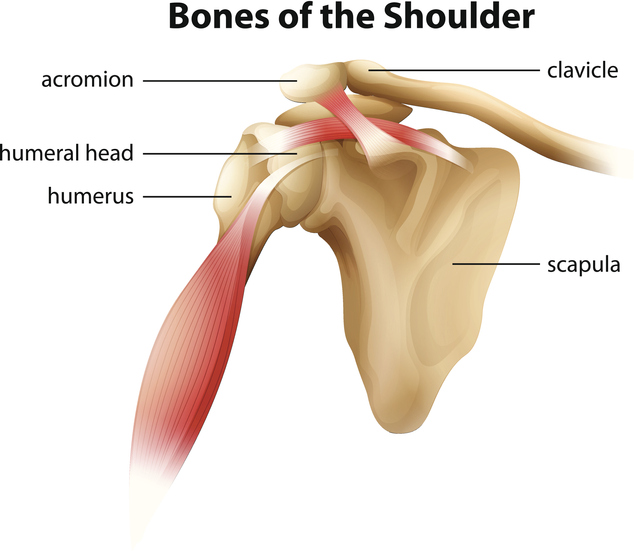

The shoulder girdle encompasses the junction between four major bones of the upper torso. They are the sternum (breastbone), clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus (upper arm). The clavicle via the sternum serves as the bony attachment between the shoulder and the trunk itself. The other two bones of the shoulder are attached to the trunk by muscles and ligaments alone.

The shoulder girdle encompasses the junction between four major bones of the upper torso. They are the sternum (breastbone), clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus (upper arm). The clavicle via the sternum serves as the bony attachment between the shoulder and the trunk itself. The other two bones of the shoulder are attached to the trunk by muscles and ligaments alone.

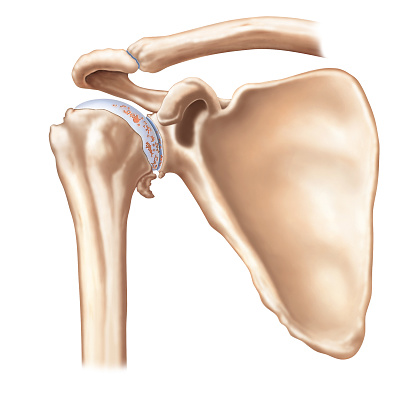

The outer end of the clavicle is attached to the scapula by the non-axial (limited to gliding movements), acromio-clavicular joint (AC-joint). The humerus is attached to the scapula by the tri- axial (ability to move in three planes) glenohumeral joint. This joint is composed of the humeral head and the “socket” (glenoid fossa) of the scapula. The unique articulative relationship of these two joints and the third joint of the shoulder girdle, the non-axial sterno-clavicular joint (located between the clavicle and the sternum) allows the shoulder to have an incredible range of motion.

Muscle and Ligament Anatomy

One of the many ways in which the shoulder joint is unique is that it derives its integrity primarily through its muscular structure, as opposed to ligamentous, cartilaginous, or other connective tissue.

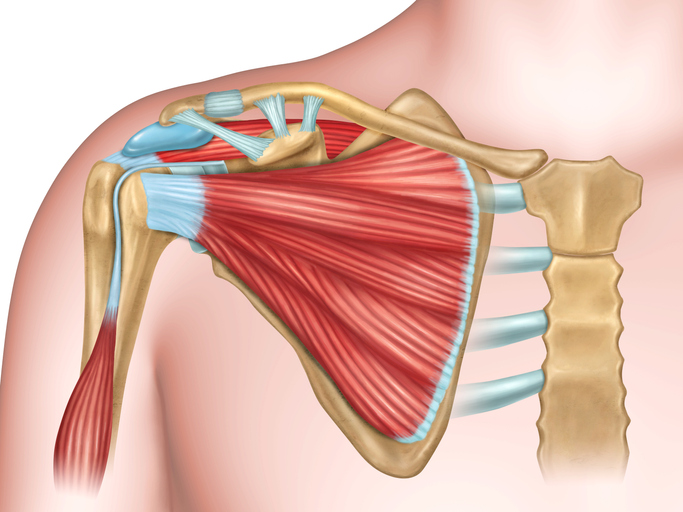

There are several groups of muscles that assist in stabilization of the shoulder joint and give it structural integrity, as well as allowing movement (both range of motion and powerful contraction). These include the anterior musculature, such as the pectoralis major, the biceps Brachii, Subscapularis, and Coracobrachialis. The “superior” muscles (deltoids, the Supraspinatus, the posterior muscles (Infraspinatus & Teres Minor), and the inferior muscles (Latissimus Dorsi, Teres Major, and the long head of the Triceps Brachii).

The muscles of primary importance when discussing injury prevention are the deltoids, including the other muscles that comprise the rotator cuff play a critical role in holding the head of the humerus in the glenoid fossa. The anterior and medial deltoids originate on the clavicle, while the posterior deltoid originates on the scapula. All three deltoid muscles insert on the humerus.

The muscles of the rotator cuff (also known as the S.I.T.S. muscle group) include the Subscapularis, Infraspinatus Teres minor, and Supraspinatus. These four muscles originate on the scapula and insert on the head of the humerus.

Sustaining a serious injury to the shoulder musculature can be quite traumatic due to the role in everyday activities that the shoulder muscles take part in.

Injuring the shoulder muscles can make it difficult for you to raise a comb to your hair, let alone perform a workout or athletic activity. One can only imagine how many thousands of shoulder injuries go unreported each year due to improper form and the use dangerous exercises.

Is the Juice Worth the Squeeze?

That is a question many doctors and physical therapists ask after an athlete or body builder has caused injury to one or multiple muscles of the shoulder from performing:

- Upright rows

- Behind the neck shoulder press

- Pull down behind the neck

- Jerking or rolling shoulder shrugs

Shoulder pain has always been one of the most common complaints of athletes who lift weights. Since the fitness boom of the early 80’s there are many more people in active exercise programs that involve lifting weights. Current research shows that lifting weights not only enhances athletic ability but increases metabolism which in turn burns more calories and reduces fat, even at rest! Unfortunately, many of these participants are doing exercises that predispose them to shoulder injuries. Some exercises are done incorrectly while others should not be attempted at all. It is important to understand functional anatomy and have a basic idea of what the muscles and surrounding structures do.

Anatomy of the Shoulder

The shoulder joint is a complex joint that has an array of movements. Its makeup allows for a variety activities such as throwing a ball, lifting a child, or cleaning that top shelf in the garage. The bony anatomy does not provide stability as well as other joints in the body. It is considered a ball and socket joint but the socket part of the joint, Glenoid Fossa is not as deep as that of the hip joint and will not keep the joint stable. This puts the joint at a greater risk for acute and overuses injuries.

The shoulder joint is a complex joint that has an array of movements. Its makeup allows for a variety activities such as throwing a ball, lifting a child, or cleaning that top shelf in the garage. The bony anatomy does not provide stability as well as other joints in the body. It is considered a ball and socket joint but the socket part of the joint, Glenoid Fossa is not as deep as that of the hip joint and will not keep the joint stable. This puts the joint at a greater risk for acute and overuses injuries.

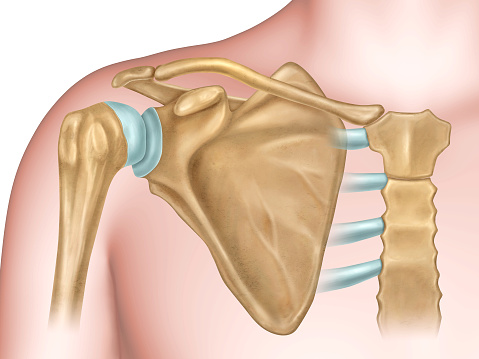

The shoulder blade, scapula, provides stability and forms another joint, A/C joint, which joins the collar bone, clavicle, with the Acromial process of the Scapula.

This structural instability of the bony surfaces makes it is very important for other structures to keep the upper arm, Humerus, from slipping out of its socket or damaging surrounding soft tissues. These structures that provide the support and stability are ligaments, muscles, tendons, and bursa. All are very important in any movement the shoulder performs. If any of these structures are compromised, an injury is a real possibility.

Anterior view of the shoulder

The Acromial process of the scapula forms the roof of the shoulder, creating a Subacromial space, in which the Subacromial bursa and rotator cuff occupy space. This space is critical when prescribing certain exercise in a strength-training program. The prime movers of the shoulder are the Pectoralis major and minor, Deltoid, Trapezius, Serratus Anterior, Levator Scapula, Latissimus dorsi, and the rhomboids. The deeper muscles of the shoulder and just as important are the four muscles that make up the rotator cuff, the Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres Minor, and Subscapularis. These are commonly referred as the SITS muscles (Figure 4.2). They pass through the Subacromial space and attach to the head of the humerus. One other muscle that is important in the shoulder is the Biceps Brachii. It has two heads, one of which attaches to the Coracoid process of the Scapula and the other, maybe more significant in the preventing of injuries, to the greater tubercle.

The Acromial process of the scapula forms the roof of the shoulder, creating a Subacromial space, in which the Subacromial bursa and rotator cuff occupy space. This space is critical when prescribing certain exercise in a strength-training program. The prime movers of the shoulder are the Pectoralis major and minor, Deltoid, Trapezius, Serratus Anterior, Levator Scapula, Latissimus dorsi, and the rhomboids. The deeper muscles of the shoulder and just as important are the four muscles that make up the rotator cuff, the Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres Minor, and Subscapularis. These are commonly referred as the SITS muscles (Figure 4.2). They pass through the Subacromial space and attach to the head of the humerus. One other muscle that is important in the shoulder is the Biceps Brachii. It has two heads, one of which attaches to the Coracoid process of the Scapula and the other, maybe more significant in the preventing of injuries, to the greater tubercle.

ROM—Range of Motion

- Flexion – the arm starts at the side of the body and elevates upward in the Sagittal plane.

- Extension – the arm starts at the side and moves backward in the Sagittal plane.

- Adduction – the arm moves towards the midline of the body.

- Abduction – the arm moves away from the midline of the body.

- Horizontal adduction – the arm starts at 90 degrees of abduction and moves toward the midline of the body.

- Horizontal abduction – the arm starts at 90 degrees and moves away from the midline of the body horizontally.

- Internal rotation – the arm rotates inward toward the midline of the body.

- External rotation – the arm rotates outward, away from the midline of the body.

Common Injuries to the Shoulder and Post Rehabilitation

A fitness specialist will find greater success in developing exercise programs that are designed in a way that decreases the chance of injuries. Some exercises are a relative contraindication while others are an absolute contraindication. This simply means individuals should avoid some exercises only if they have shoulder pain while it is best to stay away from others all together.

Common injuries that occur to the shoulder are:

- Rotator Cuff Tear

- Bicipital Tendonitis

- Shoulder Dislocation

- Bursitis

Most injuries that fitness specialist will come across will be chronic in nature, meaning it is a slow insidious onset. Many times the reason for the chronic condition is one that can be corrected. With a little knowledge and proper program development these injuries can be controlled and even prevented in the future. We will identify a few common injuries of the shoulder and exercises of concern.

What are the warning signs of a shoulder injury?

- Problems sleeping at night due to shoulder pain.

- The shoulder is stiff.

- Overhead activities cause discomfort.

- The shoulder feels like it could pop out of the socket.

- Problems with activities of daily living are encountered due to lack of shoulder strength.

Impingement Syndrome

Shoulder pain is often experienced when performing activities that bring the arm through a painful arc during overhead movements. It is notorious for causing pitchers to go on the injured reserved list during the season, but it can also affect the over ambitious exerciser who has trained too hard or incorrectly.

Subacromial impingement is one of the most common causes of shoulder pain in athletes as well as individuals involved in a strength training program. There is a space between the top of the humerus and the location where the clavicle and the Acromial process meet that allows passage of several structures. Some individuals are more prone to impingement problems due to their anatomical makeup. The shape of the acromion, which may have a more prominent “hook-like” appearance decreasing the subacromial space, can cause a greater chance of impingement syndrome.

Repetitive exercises and exercises that is performed overhead often bringing out symptoms associated with impingement syndrome.

There are basically three structures that are commonly impinged when doing certain exercises:

1. Rotator Cuff

This group of four muscles (SITS) originates on the front and back of the scapula and forms a common tendon that passes through the Subacromial space and inserts on the greater tubercle of the humerus. This tendon is one of the most commonly injured structures in the shoulder.

Specifically, the Supraspinatus muscle seems to be strained or torn more often in high intensity type activities such as throwing a baseball. These groups of muscles are more often neglected in general strength training programs of the shoulder.

The larger muscles surrounding the shoulder, deltoid and Trapezius are strengthened to a much higher degree creating an imbalance with the rotator cuff, which may explain the higher occurrence of injury to it. One of the functions of the rotator cuff is to stabilize the humerus when the deltoid contracts and elevates the humeral head upward.

If the rotator cuff is compromised or weak it will not do an adequate job of holding the humerus in place causing an impingement on the cuff between the top of the humerus and the roof of the shoulder (acromio-clavicular joint). Conversely, if the deltoids are overdeveloped compared to the rotator cuff the same effect occurs. It would be wise to include specific exercises that strengthen the rotator cuff as well as the larger muscle groups in the shoulder.

2. Biceps Tendon

This muscle has two heads, one of which inserts on the Coracoid process of the scapula and the other running through the Bicipital groove under the Acromial process to the top of the Glenoid. The same mechanism that causes the impingement of the rotator cuff can irritate the biceps tendon that attaches on the glenoid. Biceps tendon injuries can be due to impingement or may also be due to sub-luxation of the tendon out of its groove on the humerus. The symptoms associated with biceps tendon impingement or sub-luxation are generally the same. Pain is present at the top of the humerus and shoulder joint. A qualified health care professional will be able to distinguish between the two.

3. Subacromial Bursa

This sac-like structure that provides a cushioning effect in the can also become impinged causing inflammation, pain, and restricted movement in the shoulder. This is often a secondary condition and may improve with rotator cuff strengthening and flexibility.

When an individual is symptomatic it is important to follow recommended guidelines in order to decrease the chance of exacerbating the injury.

First: Modification of activities that cause pain is paramount.

Second: Avoid repetitive overhead movements.

Third: Avoid technique errors in strength training programs.

The physician often prescribes ice and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Physical therapy to restore range of motion and increase strength may be all that is needed to get back to activities of daily living. The physician may prescribe a cortisone injection in the Subacromial space to relieve any inflammation.

If conservative treatment fails surgery may be the next option. Surgical decompression, which is the actual shaving of the “hooked” portion of the acromion to create more space for the tendons and bursa, may be prescribed. After surgery physical therapy is usually prescribed to decrease symptoms of pain and swelling, to increase range of motion, increase strength and endurance and regain functional activities.

Exercises of Concern

Upright Rows

This exercise is an absolute contraindication in any weight training program. It places the shoulder in internal rotation causing the greater tubercle to abut the under surface of the Acromial process causing an impingement. This exercise is primarily working the deltoid and Trapezius, which can be accomplished by doing lateral raises and shrugs.

“Empty Can” Supraspinatus Lift

This exercise is an absolute contraindication even though it has been used in rehabilitation centers for years to isolate the Supraspinatus muscle. This internal rotation of the shoulder causes the same situation as the upright rows mentioned above. Placing the thumbs in an upward direction will keep the greater tubercle from abutting against the Acromial process.

Behind the Neck Press

This exercise is a relative contraindication in that it can cause a problem on the starting position of the exercise while overloading the joint. It puts the shoulder in extreme external rotation and the cervical region in hyperflexion. Many individuals have tight internal rotators of the shoulders causing the external rotators to do more work than they are capable of doing. This creates a situation that may place undo stress in the shoulder region causing a strain or tear to the rotator cuff. An alternative is to perform the exercise starting in front of the body at the chest level or to perform the exercise using dumbbells.

Behind the Neck Lat Pulldown

This exercise is a relative contraindication and causes the same positioning problem as the behind the neck press. An easy way to correct the problem is to do the same exercise but to end the exercise in front of the body at the chest level.

Flexibility

Flexibility and Range of Motion (ROM) are often use interchangeably but in actuality they are not the same. Flexibility occurs within the muscle while range of motion occurs at the joint, although they do affect each other in that inflexibility will limit range of motion and decreased range of motion can limit flexibility. Either way you need both to decrease the chance of injury or aid in the rehabilitation process. Physical therapists will measure range of motion with a goniometer, which will identify the range of a particular joint in degrees.

Outside of physical therapy, it is sufficient to estimate the range of motion or flexibility by comparing to the opposite limb. When there is limited range of motion at the shoulder joint due to inflexibility, starting a comprehensive stretching program would be the next logical step. When there is limited range of motion due to swelling or any internal derangement within the joint, you must proceed with caution. There should not be pain when stretching a muscle.

“No pain no gain” does not apply to stretching or strengthening exercise when returning from an injury. There may be pain when performing flexibility or strength training exercises. The key is to determine if the pain, which is mostly subjective, can cause or exacerbate an injury. Some discomfort may be necessary to increase range of motion of the shoulder but any “sharp” or “shooting “ pain within the joint is contraindicated. A static stretch is the most effective way to increase flexibility. Listed below is a series of stretches that aid in shoulder flexibility.

Shoulder Instability

Stability of the shoulder can be thought of either passively or actively. Passively the shoulder is held in place by the glenoid cavity, the labrum, the capsule, and a number of ligaments. If a person were put under anesthesia these structures would keep the shoulder from dislocating out of its joint.

Active stability is mostly a function of the muscles that surround the joint. We can directly affect the stability of the joint by performing active exercises in a strength training program. If passive stability is not present the muscles are not sufficient enough to hold the shoulder in its socket.

For instance, once a ligament is stretched it will not return to its normal length thus causing a laxity or looseness within the shoulder joint. This is why it is critical to keep the muscles surrounding the shoulder strong so that when an injury does occur the passive stabilizers do not take the brunt of the trauma.

Shoulder instability can be either a dislocation, where the humerus comes completely out of the socket, or a sub-luxation, where the humerus comes partly out of the socket and returns to its normal position. Either way it can cause trauma to the structures supporting the shoulder joint. The most common type of shoulder instability is anterior shoulder dislocation or sub-luxation. The head of the humerus pops out in front or anteriorly. This represents about 80-85% of the cases. Recently, there have been more cases of multidirectional instability where the head of the humerus can pop out anteriorly, posteriorly, or inferiorly. It would be wise to focus in on all the muscles that hold the head of the humerus in place in order to keep the joint stable.

In years past it was common for patients to be immobilized in a sling for six weeks after a dislocation. A more aggressive approach is to start range of motion once pain allows it, start isometric exercise as tolerated and avoid positions that cause discomfort (e.g. abduction and external rotation of the shoulder). The reason for early range of motion is to limit stiffness and decrease the chance of atrophy. In the post rehab phase it is important to focus on the muscles, which stabilize the shoulder. Many of the same exercises that are used in shoulder impingement will be used for shoulder instability injuries.

As mentioned earlier, the rotator cuff helps stabilize the humerus and is also vital to decreasing the reoccurrence of a shoulder dislocation. The strength of the internal rotators (pectoralis major, Subscapularis, Latissimus dorsi, Teres Major, anterior deltoid) is a good starting point in post rehab of an anterior dislocation. It is important to not neglect the opposing muscles, the external rotators (Infraspinatus, Teres Minor, Posterior Deltoid) in order to have symmetry or for multidirectional instability concerns.

Adhesive Capsulitis

Adhesive capsulitis or more commonly referred to, as “frozen shoulder” is a condition that can severely restrict the range of motion and cause pain to the shoulder. The elastic, ligamentous capsule forms abnormal adhesions causing limited motion and pain. An easy way to think of it is to image your shirtsleeve as the capsule of the shoulder. Tug on your shirtsleeve and try to raise your arm. The tension on your shirtsleeve would limit the range of motion and cause pain as the arm tries to move in a particular direction. A typical patient may be a middle-aged woman who complains of intermittent pain with perhaps a history of rheumatoid arthritis.

She avoids the pain by consciously or unconsciously using the opposite arm for activities of daily living (e.g. reaching a high object on a shelf). Eventually, she will seek medical attention, perhaps after many months of discomfort and decreasing range of motion. The physician may prescribe steroid injections in order to decrease inflammation and pain along with aggressive physical therapy to restore range of motion. During the post rehab phase much of the range of motion probably will have already been restored. It is important to identify which ranges need to be addressed more closely.

Comparing to the opposite side can do this or better yet by contacting the physical therapist or physician to see where the limitations are indicated. Either way continued flexibility and secondly strength will help restore function to the shoulder. Most patients show a gradual decrease in pain and return to normal range of motion up to a year and half. They will be out of physical therapy long before things return to normal. Typical ranges that will need to be addressed are flexion, abduction, external rotation and internal rotation of the shoulder.

General Strength Training Exercises for the Shoulder

When implementing a general strength training program for the shoulder individuals need to identify what their goals are. Often enthusiastic lifters will train the larger muscles (e.g. deltoids) while neglecting the smaller ones (e.g. rotator cuff) which are just as important in the movement of the shoulder. Any weaknesses in certain muscle groups should be emphasized in the program.

Listed below is a series of exercises that are recommended in developing shoulder strength:

Suggested Strength Training Exercises for Isolating the Rotator Cuff

Stabilization Exercise – One of the functions of the rotator cuff is to stabilize the humerus while other muscles do their job. These exercises should be done early in the program.

External Rotation exercises – this is often neglected and should be emphasized due to the imbalance of the internal rotators. The pectoralis major, Latissimus dorsi, and Teres Major overpower the weaker Infraspinatus and Teres Minor.

Internal Rotation – this exercise should not be totally ignored but concentrating on flexibility is probably more important than the strengthening aspect.

Supraspinatus Lift – lying prone on the edge of a bench with the thumb pointed upward will isolate the Supraspinatus, which is commonly injured.

Summary

The shoulder girdle is a complex area involving the humerus, scapula, and clavicle as well as many ligaments, tendons, and bursa. Its inherent mobility compromises stability and can result in injuries. We would probably see many more injuries if this were a weight bearing joint. When the shoulder is injured it can be debilitating and cause a disruption in day to day activities. Coming back from a shoulder injury can be long and painful depending on the severity of it. It is best, as with most injuries, to recognize the signs, symptoms, and act on them rather than waiting until the injury becomes a limiting factor in your daily life.

Arnold Illman, M.D., a well-known New York-based orthopedic surgeon specializes in athletic injuries to the shoulder. In the course of his work Dr. Ilman has found that true deltoid injuries, (to the deltoid muscles themselves) rarely occur because of the position and integrity of the muscle. Instead, he has defined anterior impingement syndrome (or rotator cuff tendonitis), biceps tendonitis, and A-C (Acromio Cavicular) joint damage as the three main pain-causing problems for athletes.

Mitchell Elkins. B.S., D.C., of Marietta, Ga., another expert in the field had multiple sports athlete who had suffered a major tear of the rotator cuff and the A-C joint while playing college football and then re-injured his rotator cuff while weight training. He believes as many medical professionals do that a major cause of shoulder muscle injury-as demonstrated in this particular case to be insufficient warm- up before engaging in activity. The importance of a gradual warm-up prior to exercise or physical activity cannot be overestimated in the prevention of injuries. The excuses I hear most often from body builders is, I do not have time to warm-up.

Or, the warm-up of light cardio-vascular activity will limit my muscular growth. What individuals fail to realize is once they are injured, they will have more time on their hands since they will not be able to participate in their sport or in training in the gym.

Thomas R. Caffrey, B.S., M.S. Exercise Physiologist, Certified Bio-Feedback Specialist, Tuckerton, New Jersey, found that the incidence of shoulder injury to be substantially reduced when a warm-up of 8-10 minutes of total body exercise (walking, biking, jogging, rowing) was performed followed by 1- 2 sets of the specific movement (light weight dumbbell fly before your first heavy set) prior to weight training.

The combination warm-up of General & Specific Exercise reduces the chance of injury by increasing blood flow and increasing core temperature. This physiological change increases the muscle flexibility, and brings oxygenated blood filled with nutrients that will sustain not only muscular contraction during the workout, but will actually enhance recuperation after exercise as well.

During the interviews I have conducted with these medical professionals and my own personal experience in owning a gym for more than a ten years the conclusion has been the following.

The second most preventable cause of shoulder injury is avoiding excessive straining of the muscle groups of the shoulder and upper back. Most of the injuries occur when the trainee attempts maximal poundage’s in the bench press, behind the neck press or pulldown behind the head. The following descriptions of the three most common shoulder injuries that weight trainers experience and the treatments that are most often prescribed are designed to be informative, not prescriptive.

Trained medical professionals should evaluate any injury incurred during an athletic activity.

Rotator cuff tendonitis: (also refer-red to as anterior impingement syndrome) is a problem that affects one or more of the muscles that make up the rotator cuff.

These include: Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, and Teres Mnor. These three muscles are primarily responsible for holding the ball (the head of the humerus) and socket together. In-juries most frequently occur when the arm is extended overhead and brought down forcefully, i.e., when rebounding a basketball or during certain weight training exercises, i.e., behind the-neck-press or dumbbell lateral raise above shoulder level.

These muscles become irritated when they rub against the bones under the surface of the shoulder blade (scapula). If the muscles are over-trained using the above mentioned exercises inflammation (impingement) and sometimes a slight tearing may result.

Drs. Frank Meredith, MD, and John Smith, MD, both of Manahawkin, New Jersey, have found that 9 out of 10 shoulder injuries are due to this overuse. Once rotator cuff tendonitis begins, the structures continue to swell with use and cause further irritation until the athlete is forced to stop the irritating movement(s). The diagnosis of rotator cuff tendonitis can be achieved by rotating the arm backwards keeping the elbow at shoulder level while applying light to moderate pressure to the inside of the elbow. A sharp pain described by the patient, as originating from under the top of the shoulder is usually indicative of rotator cuff injury.

The best treatments for mild injuries of this type are rest and ice. The ice should be applied to the affected area using a bag of frozen corn or peas or crushed ice. Avoid chemical cold packs applied directly to the skin due to the fact frostbite can occur, and there is not a gradual transfer of cold from the pack and heat from the muscle taking place. Using a small paper cup that has been frozen with water in it allows for a better clock-wise massage of the ice.

Treatment:

Application of between 15-20 minutes allows for deep penetration of the cold to affected areas.

Once ice is removed allow a minimum of 30 minutes for the tissue to re-warm before re-applying the ice. This ice cycle should be repeated at least 2-3 times per day. During the period of tissue re- warming the individual should be encouraged to perform gradual range of motion exercises (providing there is not extreme discomfort or pain). Excellent exercises include: clockwise and counter-clockwise circles (slow), “crawling” allowing your hand to walk like a spider up the wall with your arm out to the side of your body.

More severe rotator cuff injuries require acute care require acute care by a medical professional, usually an orthopedic physician.

Biceps Tendonitis:

A common weight training injury due to the fact of the anatomy of the path and attachment of the biceps tendon. And poor exercise form with excessive weight. First the anatomy: The long head of the biceps is connected or anchored to the shoulder by the biceps tendon, which lies in a groove (bicipital groove) on the upper arm (Humerous). This tendon is held in place by the intertubercular ligament, which when injured (bruised, torn, or over-stretched) allows the tendon to slide out of the groove.

This action causes irritation, which results in biceps tendonitis. Many times athletes will ignore a point of tenderness and train through the pain while attempting to increase size and strength.

Basic treatment for biceps tendonitis is ice; rest, avoiding exercise that aggravates the area (preacher or Scott curls, reverse grip pulldowns, to name a few).

A-C Joint Injury, “Weightlifter’s Shoulder:

This injury is many times mis-diagnosed by the layman as a deltoid injury due to the close proximity to the A-C joint. The main factors that pre-dispose an individual to this type of injury are:

- Over-training

- Poor Exercise Form

- Inappropriate Exercise Selection.

An example of the progress of this injury that typically occurs with an enthusiastic beginner during their first year of training. Unfortunately the beginner follows the advanced body builder’s routine, or he/she decides to take advice from someone else who trains that possesses little knowledge of the body or training principles. The novice is led to use poor or incorrect form, coupled with high sets and extreme poundage’s, and as a consequence over-stresses the joint and causes injury. The best treatment for mild cases of A-C injury is the same as above. Severe injury to the A-C joint typically requires surgery and rehabilitation through physical therapy, which can take a considerable amount of time.

Most lessons in life are learned the hard way, through actively experiencing them. This does not have to be the case with exercise in a gym or home setting. I have seen scores of athletes put their potential in jeopardy due to their insistence on extremely heavy lifting that place disproportionate stress on the should joint. Hopefully, possessing the knowledge of what could happen when caution and common sense are not exercised along with the muscles. We need to be intelligent enough to practice “Controlled Intensity” when we train.