Most health coaches have at least one client that complains about never feeling full when they are restricting their food intake. They find they are having to choose between suffering through the feeling of constant hunger or eating more than planned within their diet plan. The latter, more often than not, means they are eating more than their body needs.

Whether they are following a diet plan to achieve weight loss, help manage a condition or illness, or simply to eat in a way that promotes their general health, teaching your clients to recognize when they are full is an important foundational skill for them to have.

For more intuitive eaters, the concept of not knowing when you are full might seem strange. However, the ways we’ve been accustomed to eating and emotional states can have a big effect on people’s ability to recognize when they are full.

In this article, we will provide you with the information to work with your clients and help them develop the skills to recognize when they’ve had enough food.

Key Terms

Let’s look at four key terms that will help us and our clients understand the science behind feeling hungry and feeling full.

Hunger: Hunger is the uneasy sensation or feeling of weakness caused by the lack of food.

Appetite: Appetite is the desire to eat. It usually arises after seeing, smelling, or thinking about food.

Satiety: Satiety is the feeling of fullness and the suppression of the feeling of hunger that occurs after a number of signals from the body to the brain. It lasts for a period of time after a meal.

Craving: A craving is an intense or urgent desire for food. A craving can be brought on by a physiological need or a psychological desire.

The Science behind Hunger and “Fullness”

From a nutritional perspective, the role of food is to provide our bodies with energy and essential nutrients. The role of the feeling of hunger is to signal when we need to eat so our body’s cells can get that energy and nutrients. Psychological, social, and environmental factors, in addition to metabolic processes and stomach contractions, all impact hunger and satiety signals.

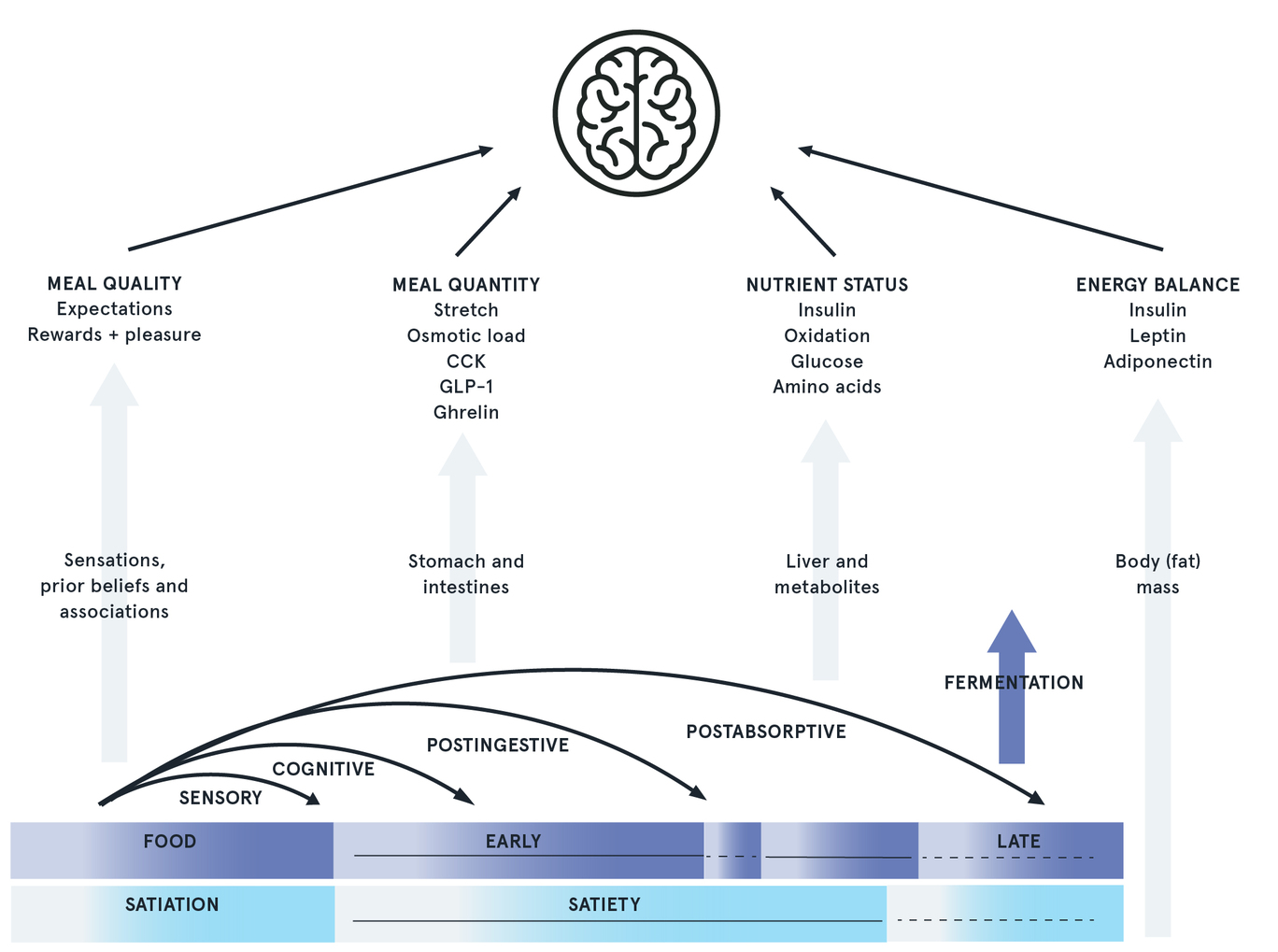

From a biological standpoint, the process your body goes through from feeling hungry to feeling full is what is called the Hunger Cascade, proposed by Blundell and colleagues.

When your stomach is empty, electrical signals from the vagus nerve detect the state of emptiness. The hormone ghrelin (the hunger hormone) is released, and low blood glucose is detected. These conditions send signals to your brain that you are hungry and motivate you to find food.

While you eat, your stomach begins to fill up, and initial digestion allows the energy and nutrients to enter your bloodstream. The expansion of your stomach and the increase of blood glucose release a hormone called leptin, which signals that you are full.

At the same time, as you begin to digest the food, your pancreas releases insulin into the bloodstream. Insulin is the hormone responsible for “unlocking” the access to cells and allowing glucose to flow in for cellular use (remember: blood glucose or blood sugar is the main source of energy for our cells).

In other words, insulin is the hormone that ensures that the cells have access to all of the energy from the food they require. This is why your blood sugar will increase shortly after eating a meal, and it will slowly decrease as your cells either use the energy or the energy is stored for later use.

Psychological factors like the feeling of pleasure and whether the meal met your expectations will also impact the feeling of satiety.

A Note about Food and Culture

Of course, food isn’t only about nutrition, or we would be fine with getting all of our nutrients from pills and supplements. Food and eating also have important social and cultural meanings—that is why humans have such a wide variety of cuisines, why we eat special foods when we celebrate, and why we offer comfort food to someone in distress.

These cultural and social meanings of food are important to maintain, but as coaches, our role is to help clients negotiate a balance between eating for pleasure and eating for health.

Why Satiety Is Important

We live in a society with enormous portions, fast food options on every corner, and marketing that constantly tempts us to overeat. Satiety is the feeling we get after we’ve had enough food or the absence of hunger. It tells us we have eaten enough and keeps us from overeating.

On the other hand, if we restrict our food intake too much, we can feel hungry and deprived, and we can lose motivation to stick to healthy eating habits or slink into a bad mood. Feeling satiated, or satisfied, after a meal is important for achieving healthful eating goals in the long term.

Note that there is a difference between feeling satisfied and feeling “stuffed.” When you feel the need to lay down after a meal, unbutton your pants, or even feel a little sick to your stomach, you’ve likely eaten more than needed to feel satisfied (think about how most people feel after a big Thanksgiving dinner). When you feel satiated you no longer feel hungry, but you still have free movement, are in good spirits, are energetic, and feel like you’ve had your fill.

When is it normal to feel hungry again after a meal? While literature varies, a good benchmark is that after a satisfying meal, you should feel satiated for at least two hours after finishing eating. If you feel like eating again before that, it is likely that there are other elements that are causing you to want to eat (see next section).

We’ll go more into detail below about how to help your clients tell the difference between feeling satiated and feeling stuffed.

Become a Certified Holistic Nutritionist Online in 6 Months or Less

Factors that Affect Your Ability to Identify When You Are Full

Social Factors

- Seeing others eat: Even if you’ve just finished a meal, seeing others eat can spark the desire to eat more in order to have a shared experience with others.

- Eating with others: Eating with others has several benefits for your mental health, but in some cases, it can also lead to overeating. The distraction from what you are eating as you are talking and the race to see who gets the last piece of pizza can lead to you to eat beyond when you feel satisfied.

Physiological and Biological Factors

- Illness and disease: Illnesses can have a significant impact on your ability to feel hunger and tell when you are full. Type 2 diabetes, for example, has the characteristic that, even after eating, the energy in the form of glucose is unable to enter the cell. When your cells still have the need for glucose that they cannot access, they send the signal to your brain that you need to eat.

- Sensory issues: Certain textures, flavors, and smells can cause people to have an increased or decreased appetite. Appetite isn’t necessarily linked to hunger—you can have an appetite even if you are full, and you can lack an appetite even if you are hungry. However, appetite is often confused with hunger.

-

Cravings: Cravings are the desire to eat specific foods. Often, cravings can feel like they are nagging at your stomach until you give in to them.

Psychological Factors

- Eating disorders: Eating disorders like anorexia nervosa and bulimia affect brain signaling that allows people to know when they feel hungry and full. If this is the case with a client you have, it is important that they seek support from an eating disorder specialist.

- Boredom: Boredom is an unpleasant feeling. It can also lead to making unhealthy choices and eating when you aren’t hungry because it helps to distract you from the feeling. Research shows that boredom can increase calorie, fat, sugar, and protein consumption.

- Anxiety and depression: Eating can momentarily distract people from the unpleasant feelings that arise when someone is anxious and depressed. The connection between anxiety disorders and eating behaviors are so close that people with early-onset anxiety are more likely to develop eating disorders.

- Distraction: This is a big one in society today. With the need to be ultra-productive and on-the-move constantly, it is not uncommon to eat when in the car, while commuting, or while rushing to finish that paper. Those who do take a break when they eat tend to pair eating with watching TV, limiting their ability to eat more mindfully.

Eating Mindfully: How to Learn to Identify When You Are Full

Mindful eating is a technique that helps you stop overeating by getting in tune with your body and learning to control your eating habits.

Mindfulness in itself is a form of mediation that arose from Buddhism that helps you recognize feelings, sensations, and emotions.

Research shows that mindful eating helps to moderate disordered eating, regulate food intake, promote weight loss, and help people make healthier food choices.

How can you help your clients implement mindful eating into their daily lives to help manage their hunger and satiety?

While there are many methods of how to implement mindful eating into your daily lives, here is a psychologist’s breakdown of mindful eating into five steps, the 5 Ss of Mindful Eating.

- Sit down: To eat mindfully, avoid eating standing up, eating in front of the refrigerator, or eating in the car. Set up a space for eating only—ideally in a dining room or at a kitchen table (no desks!). This setup allows you to give the food your full attention.

- Slowly chew: Chew your food fully—it will also help signal your brain that you have begun the eating process. If you are still having trouble pacing your eating, try putting the food in your mouth with your non-dominant hand.

- Savor: Enjoy each bite of your food. Think of the flavors, smells, textures, and ingredients that you are experiencing. Turn off all distractions that could keep you from fully savoring your food, like the TV or your phone.

- Simplify: Create an environment that will allow you to focus on what you are eating or inspire positive thoughts. What you have in view will be on your mind, so try clearing the table or putting a pleasing decoration or a bowl of fruit on the table.

- Smile: Between bites or meal components, take a moment to smile. If you are reaching the end of the meal, smile, breathe, and ask yourself if you feel satisfied.

Share the above tips or your own version of them with your clients.

Are You Really Hungry?

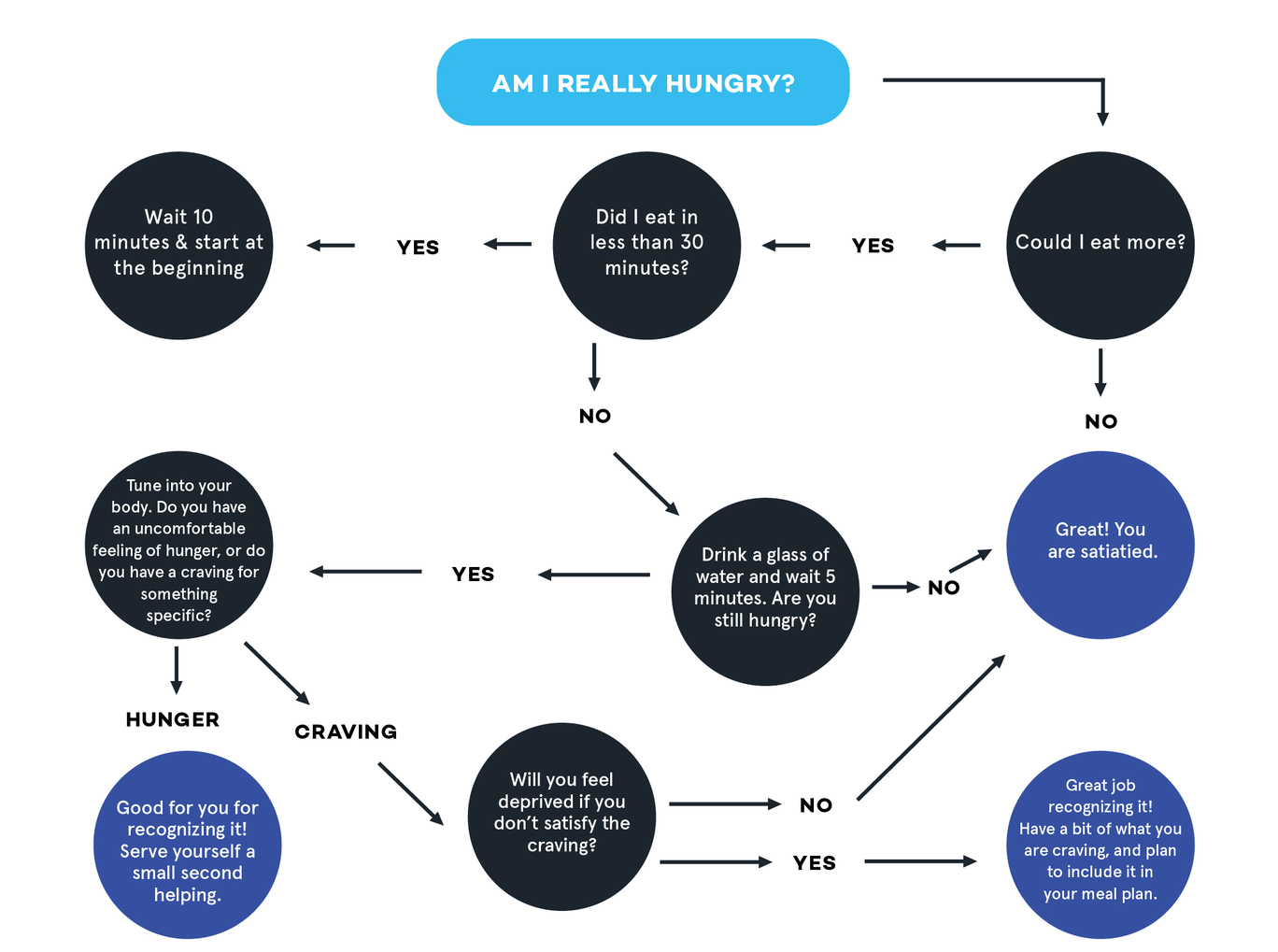

Here is an exercise you can work through with your clients to help them manage issues with overeating by helping them be more in tune with their body and promoting greater control over their eating habits.

Have them call you when they have finished a meal. Ask them, are you still hungry? Work with them through the flow chart.

Tips on Managing Cravings

Your clients might be aware that they aren’t hungry, but they still might have cravings that they are having a hard time managing.

What can you say to them that will help them manage their cravings?

Choose Nutrient-Dense and Voluminous Foods: As part of each meal, include foods that fill up your stomach, provide lots of nutrients, and are lower in energy. Voluminous foods will help signal the production of the satiety hormone ghrelin. Fruits and vegetables are foods that you can eat plenty of without consuming too many calories.

Choose Protein-Dense Foods: Include protein-rich foods, as they help signal fullness to your brain. Nut butters, seeds, and legumes are plant-based foods high in protein that will help you feel fuller for longer.

Don’t deprive yourself: If you know you tend to crave something sweet after dinner, plan for it. Know that you will have a piece of chocolate at the end of your meal, rather than feeling like you have to sneak one and then feel bad about it.

Avoid getting too hungry: Eat before you are “starving” because this feeling can cause you to overeat and give in to cravings much easier.

Drink water: Hydration is not only essential for your health, sometimes the feeling of thirst and hunger can be confused. This is especially helpful if you are still hungry after meals. Drink plenty of water before, during, and after your meals on a regular basis, and your ability to distinguish between thirst and hunger will improve.

Fight stress and anxiety: Rather than turning to the kitchen to fight anxiety, do exercise or carry out some relaxation techniques.

Wait it out: After you eat your meal, take a few minutes for the food to settle, and then ask yourself if you could still eat more. If the answer is yes, ask yourself if it is hunger or appetite that you are feeling. If you still have an appetite but feel satisfied, you can turn away the food without feeling deprived.

Hunger and satiety should be intuitive, but there are so many social, environmental, and health-based factors involved in the process that we can become accustomed to overeating. It is important to teach your clients how to be in tune with their bodies to prevent overeating.